The 2025 Reality Check: Emulation's Limits and Qualcomm's Beachhead

The spring 2024 launch of Qualcomm’s Snapdragon X CPUs for Windows PCs arrived with significant fanfare, promising a new era of AI PCs and, crucially, capable gaming performance. The reality for gamers a year later is more nuanced. The core challenge remains a fundamental one: software. The vast, sprawling library of PC games is built for x86 instructions, not Arm. On today’s Snapdragon X systems, gaming is an exercise in translation, heavily reliant on software emulation through Microsoft’s Prism layer.

This isn't to say progress hasn't been made. A critical late-2024 update to Prism added support for AVX/AVX2 instructions and, perhaps more importantly, native anti-cheat support, starting with Easy Anti-Cheat. This single update allowed titles like Fortnite to finally run, breaking a major barrier that had blocked countless multiplayer games. It was a necessary, incremental step forward, not a breakthrough.

The present state of Arm gaming is thus defined by a paradox: these chips, like the announced second-generation Snapdragon X2, possess powerful, modern CPU cores that analysts suggest could rival or exceed current x86 chips in single-core performance when running native code. Yet, for gamers, that potential is hamstrung by the emulation overhead. Qualcomm successfully established a beachhead, proving Arm can work in a Windows PC, but the territory of native, high-frame-rate gaming remains largely unconquered.

The New Contenders: Nvidia's Power Play and Valve's Stealth Build

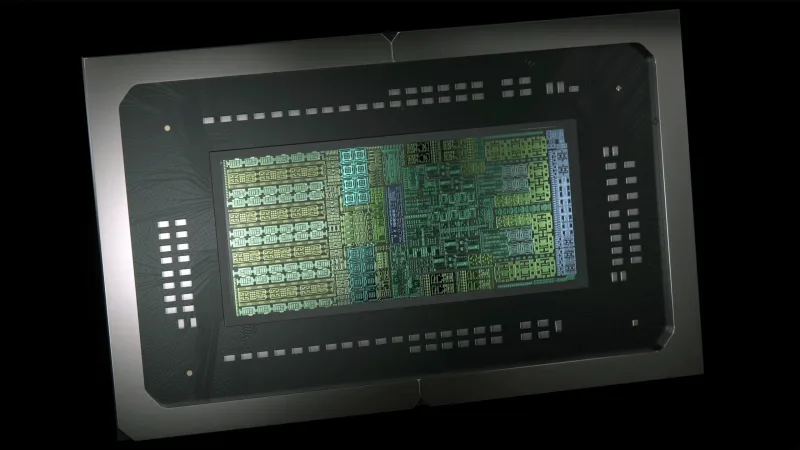

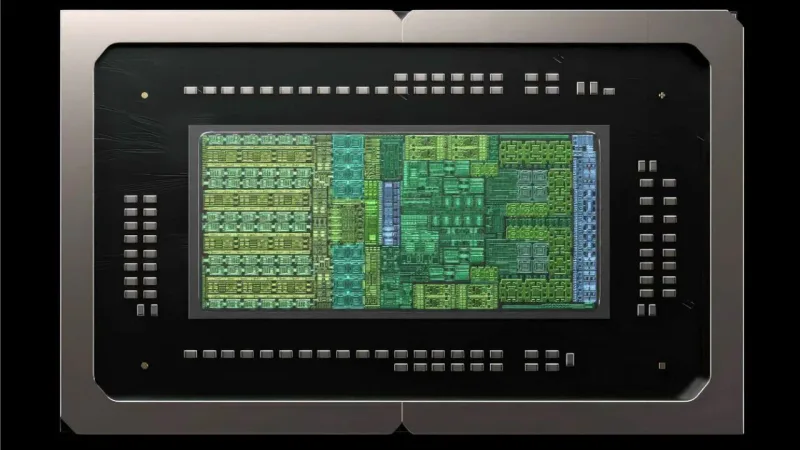

If Qualcomm’s role was to prove viability, the next wave of entrants is about to redefine the potential. The most significant confirmation came from Nvidia, which announced its entry into the PC Arm CPU arena with a chip based on its GB10 superchip. Nvidia’s move is a potential game-changer for one primary reason: graphics. The company claims its integrated graphics will offer performance comparable to a desktop RTX 5070. If true, this would instantly make it the most powerful graphics solution in any Arm-based APU (a combined CPU and GPU on one chip) by a colossal margin, directly addressing the integrated graphics limitation of current designs.

However, Nvidia’s first chip introduces a fascinating complication. Reports indicate it will use standard off-the-shelf Arm Cortex cores (X925 and A725). Unlike Qualcomm’s or Apple’s custom designs, these cores lack dedicated hardware features to accelerate x86 emulation. This could force a significant re-engineering of Microsoft’s Prism layer to maintain compatibility, highlighting the growing pains of a fragmented Arm ecosystem.

Meanwhile, in a parallel universe, Valve is executing a classic stealth build. The company has developed a version of SteamOS for Arm to power its new Steam Frame VR headset (which uses a Qualcomm Snapdragon 8 Gen 3 chip). Crucially, this build includes Valve’s own x86-to-Arm translation layer, FEX. While focused on VR hardware today, Valve’s deep platform expertise and ownership of the world’s largest PC gaming storefront make it a wildcard with the unique potential to build a tailored, gaming-first Arm ecosystem from the ground up.

The New Contenders: Nvidia's Power Play and Valve's Stealth Build

The Core Technical Advantage: Why Arm is a Threat on Paper

Beneath the current software hurdles lies the compelling technical argument for Arm’s ascent. Performance analysis suggests that the latest custom Arm cores, such as those in Apple’s M5 and the upcoming Qualcomm Snapdragon X2, likely possess superior single-threaded performance to contemporary Intel and AMD x86 CPUs when executing native code. Single-threaded performance remains the bedrock of gaming performance, driving physics, draw calls (instructions sent to the graphics card), and game logic.

This raw potential on paper is what makes the current situation so tantalizing and frustrating for proponents. The x86 ecosystem’s advantages are not primarily about silicon (chip design) today; they are about decades of entrenched software support. Every game, driver, and utility is built natively for x86, and the platform seamlessly supports the vast ecosystem of discrete GPUs from Nvidia and AMD. Arm’s challenge is not to match x86 performance in emulation—it’s to build an ecosystem compelling enough that developers start compiling natively for Arm, unlocking that theoretical performance lead.

The Path to War: Breaking the Chicken-and-Egg Cycle

Given this paper advantage hamstrung by ecosystem barriers, breaking the cycle requires specific catalysts. So, when does the "epic battle" truly begin? The consensus is that a mass Arm revolution is not imminent for 2026. Three major hurdles stand firmly in the way:

- Reliance on Emulation: Performance will always be sub-optimal versus native code.

- Lack of Native Game Ports: Developers have little incentive to spend resources on a tiny market.

- No Discrete GPU Platform: High-end gaming is inseparable from powerful discrete graphics.

Breaking this cycle requires a catalyst. The tipping point could be a major game engine—like Unreal Engine or Unity—offering first-class, streamlined native Arm support, dramatically lowering the porting barrier. Alternatively, it could be a hardware platform so compelling that developers are forced to prioritize it. Nvidia’s GB10-based chip, with its promised RTX 5070-level graphics, is the first candidate with that kind of disruptive potential. If it delivers a gaming experience that rivals mid-range x86 desktops in a laptop form factor, the calculus changes.

Each player has a role in this ecosystem puzzle. Qualcomm must continue refining its silicon and working with Microsoft on emulation. Nvidia needs to deliver its promised graphics leap and ensure software compatibility. Microsoft holds the keys to the Windows ecosystem with its Prism layer. And Valve, the dark horse, could leverage SteamOS and FEX to create a streamlined, alternative gaming platform that bypasses Windows entirely.

While the mass transition of PC gaming to Arm did not happen in 2025, the strategic pieces are now irreversibly in motion. The question is no longer if Arm will become a major player in PC gaming, but when and how. The coming years will be a critical period of ecosystem building, where victory may be determined not by who has the fastest silicon in a benchmark, but by who best solves the intricate software and developer support puzzle. For gamers, the most immediate sign of progress to watch will be the first major AAA game announced with a day-one native Arm port—that will be the opening salvo in the true battle for the future. The die is cast. The armies are marching. The epic battle for the architecture of our gaming PCs is finally, authentically, beginning.

Comments

Join the Conversation

Share your thoughts, ask questions, and connect with other community members.

No comments yet

Be the first to share your thoughts!